Economy

Inflation

Inflation in the US hit its highest level in 40 years, two years ago. It went up in 179 of the 194 countries around the world since 2020. Since then, global inflation has slowed, which has led people to hope that prices paid by customers will soon return to normal.

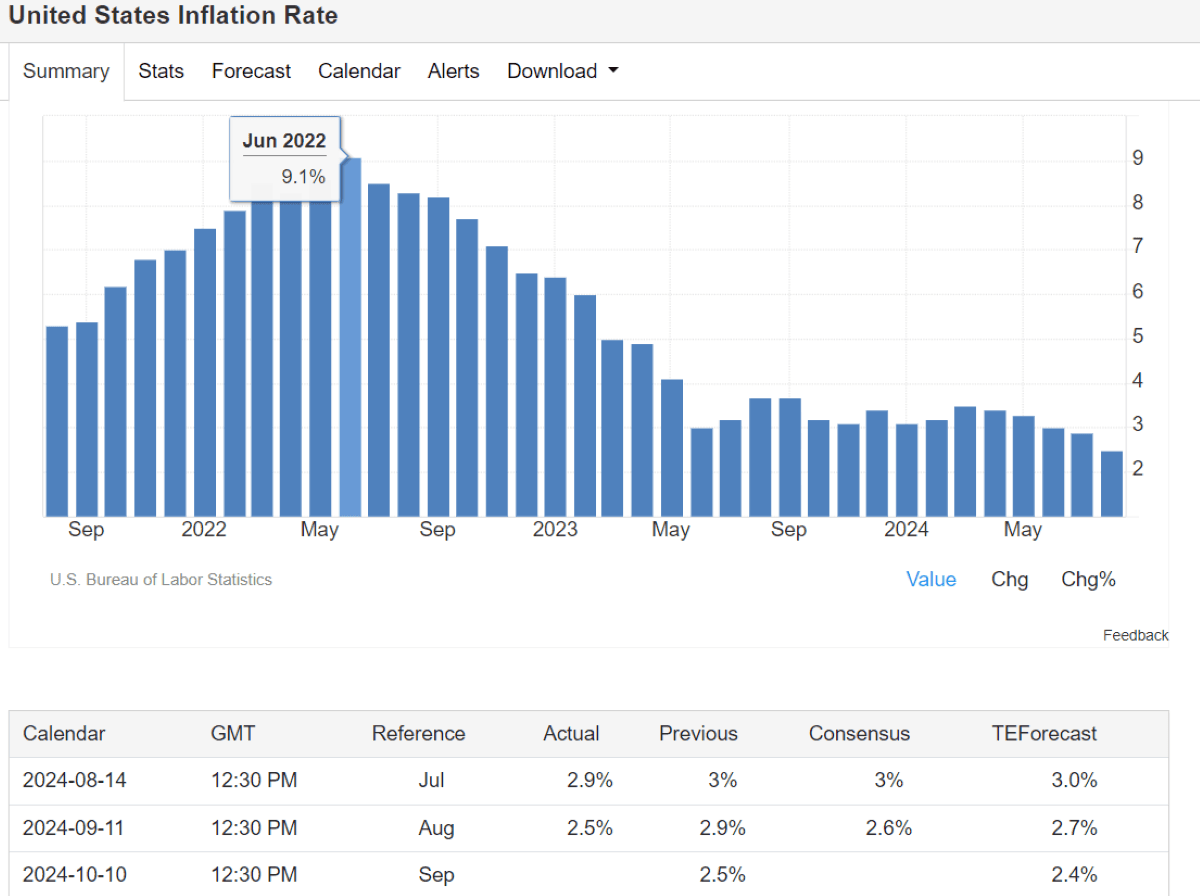

In the US, the yearly inflation rate fell for the fifth month in a row, to 2.5% in August 2024. This was the lowest rate since February 2021, down from 2.9% in July and below the 2.6% rate that was expected. Gasoline prices dropped by 10.3% compared to -2.2% in July, fuel oil prices dropped by 12.1% compared to -0.3%, and natural gas prices dropped by 0.1% compared to 1.5%. Food inflation went down from 2.2% to 2.1%, and transportation inflation went down from 8.8% to 7.9%. Prices kept going down for both new and used cars and trucks, 11% vs. 1% and 10.4% vs. 10.9%. But prices went up a little more for housing (5.2% vs. 5.1%) and clothes (0.3 vs. 0.2%). The CPI went up 0.2% from the previous month, which was the same as in July and what was expected. The major reason for the monthly rise was the 0.5% rise in the shelter index. At the same time, core inflation stayed at 3.2%, which is the lowest level in over three years. However, the monthly core inflation rate rose from 0.2% to 0.3%, which was higher than the 0.2% goal. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics is the source.

Consumer prices will not go back to how they were before inflation goes down; that’s the bad news for the economy. They will just stop rising so quickly and sharply.

Also, it’s important to note the difference between core inflation, which is the most important measure of the Consumer Price Index, and total inflation. The first one includes food and energy prices, which change more quickly and depend more on seasonal factors. The second one does not include food and energy prices because they change so much. Core inflation stays the same for longer because the price of gasoline changes more than the price of cars that use gasoline.

If lawmakers want to fight inflation right away, they can tell the central bank to raise interest rates. This slows down loans, which in turn slows down the economy as a whole, which causes prices to rise. But sometimes the cure is worse than the disease as in the case of our economy. For example, if central bankers raise interest rates at the wrong time or to the wrong amount, it can cause a recession. This is why they tend to be very careful. That being said, this cautiousness might have stopped people from taking the bold steps that were needed to deal with and control the huge rise in prices around the world after the 2020 pandemic.

Let’s go back. Prices didn’t go up by much in 2020, when the pandemic was just starting and when it was at its worst. On the other hand, things quickly and sharply went up when lockdowns were lifted and some normal economic activity returned in early 2021. Central bankers around the world may have been too hopeful because many countries were releasing vaccines almost at the same time. They often said that the first rises in inflation were just “blips” that would go away soon.

They were definitely right about the main reason for those errors: The world economy was seriously affected by COVID-19. Because of problems in the supply chain, consumers and businesses could not get what they wanted or needed. This caused demand to far exceed supply, which drove prices up. They didn’t expect that new types of the virus would keep appearing, that so many people would fight against or completely refuse mask laws and vaccines, or that the spread of vaccines around the world would be so unequal and uneven. Because of a once-in-a-lifetime outbreak, supply chain problems happened all the time.

But there was a second reason why central bankers didn’t stress how dangerous inflation was for our economy. Being able to convince businesses and customers that everything is okay is an important part of their job. This is because businesses raise prices to prepare for cost increases, which makes people think that prices will keep going up. Prices often go up because people are scared more than because costs are going up.

When people start to worry about inflation, a company that doesn’t change its prices very often, like a car company, will protect its profit margins by preparing for predicted future inflation and, if it has already started to see higher costs, making up for past inflation as well. At that point, words like “blip” start to show up less in headlines and words like “temporary” and “transitory” start to show up more. It’s still not clear what “temporary” and “transitory” mean in general. There is also a rise in pay. Workers want higher wages to keep up with the rising cost of living when they think everything will cost more. When companies pay their workers more, they have to raise prices to cover the extra costs. As prices rise, wages rise, which makes prices rise even more. This is the vicious process of consumer price inflation.

The fact that inflation has been stable even though central banks have been raising interest rates steadily for years shows some new aspects of the time after the pandemic: The inflationary depression may be caused in large part by companies merging and markets becoming more concentrated. Many businesses have raised prices much more than the rise in production costs, citing inflation as an excuse. As a result, they have had some of their best financial quarters and biggest profit margins ever. One well-known example of this is asthma inhalers, whose prices have gone from about $10 a decade ago to $100 now, even though the costs of making them haven’t changed much. This is why new words like “shrinkflation” (when a product gets smaller or lighter without its price going down) and “greedflation” (when goods’ prices go up without their production costs going up) have started showing up in our newsfeeds. The tools that central banks have don’t give them much power to stop either of these things from happening or the economic pressure that they cause. Companies that have a strong hold on the choices of buyers can set prices however they want.

So what happens when inflation keeps going up instead of going down or slowing down? Not a good thing. One option is “stagflation,” which happens when the economy stops growing, unemployment stays high, and inflation stays high. The worst-case situation for central bankers is hyperinflation, which happens when prices rise too quickly and the value of the currency falls so fast that it seems like it can’t be stopped, like in Weimar Germany after World War I. But hyperinflation can be seen today, not just in the past. Zimbabwe has had problems with rising prices for more than ten years. The IMF predicts that Venezuela’s inflation rate will reach 250% this year, which, believe it or not, is a huge improvement from the five-digit rates of a few years ago. Sudan is expected to come in second with an inflation rate of about 145%. Argentina’s inflation crisis propelled an unlikely far-right candidate to the presidency, and many other countries will see price increases many times higher than the 2% level that most central banks set as their ideal inflation target. Additionally, hyperinflation is the best example of how mass expectations affect the prices of goods and services. When millions of people think that their currency will be worth a lot less tomorrow, people and businesses start to reject the national currency in favor of alternatives like cryptocurrencies or maybe the U.S. dollar.

The other end of the spectrum is chronic deflation, which is when prices keep going down. When prices keep going down, it means that the economy is getting weaker because people aren’t spending much and not making much. This means that wages are also going down, which makes even less desire for goods and services and even lower prices. The same is true for deflation as it is for inflation: Greece went through a deflationary phase during the debt crisis because it had to cut wages and pensions as part of its loan terms. The country quickly went back into deflation after the pandemic started. This cycle had been going on for twenty years in Japan’s economy. It wasn’t publicly declared to be in deflation until last March, which ended decades of negative interest rate monetary policy. Next is Switzerland, which caused deflation and had to deal with it for many years, though it also gained from it. The country kept its exports going by using very low interest rates to fight the value rise of its currency, which many experts still don’t understand. At the same time, it avoided the worst effects of deflation, like a crippling drop in economic activity or high unemployment. Not until 2022, when inflation hit a 30-year high of 2.8%, did things start to change. To fight it, the Swiss National Bank had to raise its policy rate from -0.75% to 1.5%.

All of these strange situations show why there isn’t a single way to fix the many problems caused by inflation. Also, just when you think a problem is over, another one can appear out of nowhere. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, energy costs were already going up. The invasion of Ukraine by Russia and the war between Israel and Gaza made things much worse.

After all this time of higher inflation around the world, will it ever end? The most important thing we’ve learned in the last few years is that it’s hard to tell what will happen in the future when it rests so much on viruses, dictators, business leaders, and yes, even customers. There are, however, signs of improvement. The IMF says that inflation is falling faster than expected in most areas. It is expected to reach 5.8% globally in 2024, with only 50 countries seeing it rise above last year’s levels. For now, central bankers will have to use a lot of different kinds of data all the time to make their decisions and policies better. They will have to “kick the tires” of the economy as they go.

The Stock Market

To close out the Trump administration on January 19, 2021, the Dow Jones Industrial Average jumped 257.86 points, or 0.8%, to a new closing high of 31,188.38. The S&P 500 advanced 1.4% to a record close of 3,851.85, led by the communication services sector. The tech-heavy Nasdaq Composite jumped nearly 2% to 13,457.25, notching a fresh record. All three averages also touched their intraday highs during the session.

In contrast, under the President Biden and Kamala Harris administration on September 19, 2024, the Dow closed 522 points, or 1.3%, higher, reaching a new record after passing the 42,000 level for the first time. The S&P 500 rose 1.7%, topping 5,700 for the first time and also closing at a fresh high. The Nasdaq Composite added 2.5%.

Manufacturing

More than 200,000 manufacturing jobs were lost during Trump’s single term. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic manufacturing job growth had all but plateaued under the Trump administration.

Since President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris took office in January 2021, more than 775,000 manufacturing jobs have been added to the economy. The growth is expected to continue, with the Biden-Harris Inflation Reduction Act estimated to create 336,000 manufacturing jobs a year until 2035.

In contrast, more than 200,000 manufacturing jobs were lost during former President Donald Trump’s single term. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, manufacturing job growth had all but plateaued under the Trump administration.

Oil Drilling

Oil prices averaged close to $100 per barrel from 2011 to 2014, leading to record drilling activity. But Saudi Arabia initiated a price war in late 2014, aiming to reclaim market share lost to U.S. shale oil.

That price war—which I called OPEC’s Trillion Dollar Miscalculation—ultimately crashed oil prices to below $30 per barrel. Gasoline prices also sharply fell during that period. In response to low prices, the rig count plummeted in Obama’s last two years.

Under President Trump, oil prices rose during his first two years, reaching $65 per barrel in 2018 (source). The rig count followed oil prices higher. However, the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 crushed oil prices globally, causing the rig count to collapse to its lowest level since 2009.

The price of oil would recover sharply in 2021, and then in 2022, it would surge to above $100 for the first time since 2014. Several factors drove oil prices higher. One, some U.S. production was lost during the pandemic crash. Some producers went bankrupt, and others permanently shut in marginal production. Second, OPEC —at the request of President Trump —sharply cut production in 2020.

When the economy began to strongly recover, loss of production from U.S. producers and lower production from OPEC helped cause prices to surge. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was the final catalyst that drove oil prices back over $100.

Although the rig count has rebounded under President Biden from the pandemic lows, it remains lower than in previous years. Biden’s administration has averaged 500 rigs, compared to 666 under Trump and 909 under Obama. Despite this, average oil production under Biden has been 12.2 million barrels per day (BPD), compared to 11.0 million BPD under Trump and 7.2 million BPD under Obama.

Jobs

Biden has a huge edge over Trump at the highest level.

Total nonfarm payrolls, the most common way to measure total employment and the group that most American workers belong to, show that the U.S. gained about 16 million jobs in Biden’s first 43 months in office, but lost 2.7 million jobs during Trump’s.

In the same way, the jobless rate went up by 1.7 percentage points under Trump, from 4.7% to 6.4%, and then went down by 2.2 percentage points under Biden, to its current level of 4.2%.

Wage growth has been a little faster under Biden than under Trump. So far, average hourly wages have grown by 17% under Biden, compared to 15% under Trump.